By: Dennis M. Germain, Macomb Family Law & Divorce Attorney

INTRODUCTION

This article is Part Two of the series, “Dividing Property & Debt in a Michigan Divorce.” When it comes to dividing property and debt in a divorce case, clients often ask me questions such as:

“Is the home I purchased prior to the marriage my separate property in a divorce?”

“Will my husband get a portion of my pension or other retirement accounts in divorce?”

“Do I get to keep my wedding ring in a divorce?”

“Will I have to take on my wife’s debt in a divorce?”

“In a divorce, how do I know what items are subject to division and what items are not?”

This article outlines a framework to assist in answering these questions. The previous article focused on inventory (itemizing and valuing) of the parties’ property and debt in a divorce (part 1). This article focuses on the characterization stage of the analysis, which involves determining what items should be classified as marital property and debt and what items should be classified as separate property and debt (part 2). The two articles to follow will focus on determining equitable division of assets and debt in a divorce (part 3), and identifying if invasion of a party’s separate estate might be applicable (part 4). FN1.

GENERAL RULES FOR CHARACTERIZING PROPERTY & DEBT IN DIVORCE

When characterizing whether property and debt is subject to division in divorce, history shows that the higher courts of Michigan have generally accepted the idea that there are two major categories of property and debt; first, “marital” property and debt, and second, “separate” property and debt. The significance of an item’s characterization is that marital property and debt is typically subject to equitable distribution among both spouses upon divorce, whereas separate property and debt, absent exception, is not subject to such division. In some instances, particularly in a high asset divorce, the debate on characterization of certain items of property or debt can have an enormous impact on a party’s bottom line award from the divorce.

Michigan statute and case law can be quite vague, ambiguous, and even inconsistent on this topic. So much so that many highly respected family law attorney-scholars advance materially different interpretations of what items should be subject to division under the statutory and common law framework they are confronted with. Without going through the history and evolution of this topic (which would cause the number of footnotes in this article to increase to about a hundred), this author asserts his opinion that the general rules below comprise a decent way of mechanically summarizing how the categories of marital and separate property and debt operate under the current state of affairs in Michigan.

Presumed “marital” property and debt generally entails:

- Items Accumulated During the Marriage: Items or portions of items of property and debt accumulated during the marriage or due to activity that occurred during the marriage (regardless of whose name the items are titled or assumed in, and regardless of who actually was individually responsible for accumulating the items or portions thereof), except for certain items or portions thereof accumulated by an individual during the marriage through gift, inheritance, possible passive appreciation, or other obscure legal exception; and

- Separate Items that Mutated into Marital Items: Items or portions of items of property and debt that would have once been treated as separate items, except that activity occurring during the marriage, such as commingling, caused them to mutate into marital items (keep reading below for a further explanation on the concept of commingling).

Presumed “separate” property and debt generally entails:

- Items Accumulated Prior to the Marriage: Items or portions of items of property and debt accumulated by a spouse prior to the marriage, that have been preserved by that spouse as separate, and have not been commingled into the marital estate;

- Items Accumulated During the Marriage Subject to Exception: Items or portions of items of property and debt accumulated by a spouse during the marriage, that have been preserved as separate by that spouse, have not been commingled into the marital estate, and/or fall into one of the following exceptions:

- Gift or Inheritance: The item or portion thereof was accumulated during the marriage by one spouse through gift or inheritance, and was titled, delivered, and/or intended by the donor to belong to one spouse and not the other spouse;

- Articulable Premarital Activity: The item or portion thereof was accumulated by one spouse during the marriage but primarily due to articulable premarital activity of that spouse;

- Appreciation, Depreciation, or Buildup: The item or portion thereof was accumulated by one spouse during the marriage primarily through appreciation, depreciation, or the buildup of a separate item;

- Obscure Legal Exception: The item or portion thereof would otherwise be treated as a marital item, but for a legally recognized exception that instead characterizes it as a separate item.

NOTES ON COMMINGLING

In this author’s opinion, commingling is a judicially-made concept in Michigan. Commingling is the process by which an item that was previously a separate item is mixed with marital items beyond traceability and/or treated with certain intent that it lost its characterization as a separate item and transformed into a marital item.

In this author’s the opinion, guidance from Michigan case law is all over the map when it comes to determining whether or not a separate item has transformed into a marital item through commingling. Although this case is rarely cited, because it is unpublished, this author asserts that the Michigan Court of Appeals case, Landry-Chan v Poh Haut Chan, provides some of the most comprehensive guidance for analyzing whether a premarital item should be treated as commingled. FN2.

The major take away from Landry-Chan case is that when analyzing whether or not separate property has been commingled (and thus has mutated into marital property) you look to two major components; (a) tracking, and (b) intent. FN3.

As to “tracking,” the question is: Is the current value, balance, or equity in the item in question readily traceable back to the original item of separate property (versus all mixed up with marital items to where one cannot tell what is what)? The better one is able track the item in question back to separate property, the more likely it is to be characterized as separate property.

As to “intent,” the question is: Did the party who once held the item as his/her separate property engage in behavior during the marriage that indicates he/she intended to make the item part of the marriage? The more that it looks like the party originally holding the separate property treated the property as a joint marital asset during the marriage (e.g., transferring the item into both parties’ names, regularly referring to it as both parties’ item, allowing the other party free access to the item, etc.), the more likely it is to be characterized as marital property.

SOME EXAMPLES REGARDING “MARITAL” PROPERTY & DEBT

Now that we have set forth a framework, let’s apply some examples to the general rules set forth above. Some examples of items that might be treated as “marital” property or debt are listed below.

Employment Earnings Earned During the Marriage

Example: The husband primarily stayed home and cared for the children during the day, and was not employed. The wife earned a paycheck at General Motors during their marriage and deposited the corresponding funds into her separately-titled account at Friendly Macomb Credit Union. One of the parties files for divorce.

Author’s Analysis: The corresponding funds held in the wife’s separate account should be characterized as marital property because they were accumulated during the marriage, and thus should be subject to equitable division of the marital estate upon divorce. FN4. Who individually earned the paycheck and whose name is titled on the account to which the corresponding funds were deposited are immaterial considerations under Michigan Law.

Unilateral Incurrence of Credit Card Debt During the Marriage

Example: During their marriage, the husband, without the wife’s approval or knowledge, using a credit card in his own name, purchased hunting equipment that only he will use in his off-time, thereby incurring $3,500.00 in debt. One of the parties files for divorce.

Author’s Analysis: The debt is likely to be presumed as marital debt because it was accumulated during the marriage. It should thus be subject to equitable division of the marital estate upon divorce. FN5. A hobby that seems on its face to benefit only one spouse and not the other is typically a regular incident of marriage. However, even though the debt is likely to be characterized as marital; depending on the totality of the circumstances, Wife might later have an opportunity to argue that equitable division necessitates husband’s disproportionate assumption of credit card debt.

Commingling & Premarital Funds Deposited into Joint Account During Marriage

Example: During their marriage, the husband and wife opened up a joint account at Shelby Township Christian Bank. The husband deposited $75,000.00 into the account from his premarital funds. The wife deposited $35,000.00 into the account from her premarital funds. The parties each assigned each other as survivor beneficiaries on the account, and each party had open access to the account. For the next ten years of their marriage, the parties regularly deposited their employment earnings into the account, paid routine marital expenses from the account, and transferred a large amount of funds from the account into other investment accounts that were created during the marriage. Thereafter, one of the parties files for divorce.

Author’s Analysis: The funds remaining in the account at the time of the divorce are likely to be treated as marital property. Each party’s separate initial contribution to the account was previously understood as premarital separate property. However, the commingling of the separate property with other marital property, combined with marital spending, likely caused each party’s separate initial contributions to mutate into marital property. The acts of the parties were indicative of a single economic unit and appeared to reflect that the parties, throughout their marriage, intended for the funds in the account to be part of the marriage. Furthermore, due to mixture of premarital assets with marital activity through a large number of transactions relative to the account over a noteworthy period of time, it is likely very difficult to properly track the transactions directly back to premarital assets. FN6.

SOME EXAMPLES REGARDING “SEPARATE” PROPERTY & DEBT

Next, let’s apply the general rules above to look at some examples below where items are likely to be treated as “separate” property or debt.

Savings Account Funds Accumulated Prior to the Marriage

Example: Prior to her marriage with her husband, the wife had $55,000.00 in her savings account at the local Sterling Heights Christian Credit Union, an account that was titled in her name only. During the marriage, the wife separately maintained the funds in that same account under her name only and no activity was conducted on the account (except for nominal interest accrual). One of the parties files for divorce.

Author’s Analysis: The $55,000.00, plus interest accrued, should be characterized as wife’s separate property, and should not be subject to division upon divorce. FN7.

Equity in Home Accumulated Prior to the Marriage

Example: The husband retained outright ownership (with $0.00 owed on any mortgage or otherwise) of an eleven acre parcel of land in northern Michigan long before his marriage to the wife. When the parties were married in 2005, the property was worth approximately $200,000.00. Today the property is worth about $350,000.00. I.e., the house appreciated in value by $150,000.00 during the marriage. During the marriage, no improvements or maintenance were made on the property. However, the husband paid property taxes relative to the property during the marriage. One of the parties files for divorce.

Author’s Analysis: The premarital $200,000.00 of equity in the property should be treated as the husband’s separate property, and thus should not be subject to division upon divorce. Furthermore, husband maintains a strong argument that the $150,000.00 appreciation in value on the property was due only to passive market forces and not actually work conducted during the marriage, and thus should also be characterized as his separate property. The payment of property taxes alone is unlikely to be deemed sufficient marital activity to have the separate property re-characterized as marital property. As a general rule, de minimis efforts expended toward the appreciation of separate property does not cause the appreciation of an item to be classified as marital property. Moreover, any appreciation of an asset that is wholly attributable to market forces beyond the spouses control is passive appreciation. In the instant case, the appreciation in the value of the property was passive because there is no causal nexus between actions on the property taken during the marriage and the appreciation of the value of the property. The husband should argue that the payment of taxes on the property during the marriage was nothing more than “de minimis,” “ministerial” action, and was immaterial to the property’s increase in value during the marriage. FN8.

Retirement Interests Accumulated Prior to the Marriage

Example: Prior to their marriage, the husband had accumulated ten years of credit on his Chrysler pension, and the wife had accumulated $250,000.00 in her Henry Ford Hospital retirement savings plan 401(k). During the marriage, the husband accumulated an additional eight years of credit on his pension, and the wife accumulated an additional $95,000.00 in her 401(k) plan. One party files for divorce.

Author’s Analysis: The husband’s ten years of premarital pension credit and the wife’s $250,000.00 of premarital 401(k) interests should be characterized respectively as each person’s separate property, and thus should not be subject to division upon divorce. With the assistance of an expert, the wife might be able to maintain an argument that all investment gains passively accumulated off of the $250,000.00 premarital portion of her 401(k) should also be treated as separate property. The husband’s additional eight years of pension credit and the wife’s additional $95,000.00 in her 401(k) plan, should be treated as marital property, and thus should be subject to division upon divorce. FN9.

Student Loan Debt Accumulated Prior to the Marriage

Example: Prior to the marriage, the wife accumulated $45,000.00 of student loan debt relative to her pursuit of a teaching degree at Michigan State University. During the marriage, the husband and the wife contributed to paying off a portion of the debt with funds accumulated during the marriage. By the time one of the parties filed for divorce, Wife had about $25,000.00 remaining on her student loan debt.

Author’s Analysis: The remaining $25,000.00 of the wife’s student loan debt should be treated as her separate debt, and thus is not subject to division upon divorce, because it was accumulated prior to the marriage. FN 10.

Gift Acquired During the Marriage

Example: The wife received a boat from her father as a present for her 40th birthday. The boat had wife’s name painted on the hull. The boat was titled in the wife’s name only. At the time she received the gift, the boat was valued at about $45,000.00. Two days later the husband and the wife used funds from their joint marital bank account to have an expensive motor installed on the boat, thereby causing the boat to appreciate to a value of $52,000.00. No other improvements on the boat were made. Three days following the improvement to the boat, one of the parties files for divorce.

Author’s Analysis: The $45,000.00 in equity relative to the boat is the wife’s separate property, and thus not subject to division upon divorce, because it was acquired via a gift made exclusively to her, and maintained as a separate asset. FN11. However, the $7,000.00 increase in value is likely to be treated as marital property because it is relative to active appreciation traceable to improvements made using marital funds. FN12.

VA Disability Interests Accumulated During the Marriage

Example: The husband served his entire military career during his 41 year marriage to the wife. The husband accumulated interests in VA disability benefits that led to his receipt of monthly VA disability compensation payable to him. One of the parties files for divorce.

Author’s Analysis: Although the husband’s interests in VA disability benefits were accumulated entirely during the marriage, 100% of his interests in said benefits should be characterized as his separate asset, and thus are not subject to division upon divorce. The Uniform Services Former Spouses’ Protection Act renders VA disability compensation exempt from division upon divorce. FN13. This instance is one of the legal exceptions to the presumption that items accumulated during that marriage should be characterized as marital items subject to division upon divorce. Other examples where assets seemingly accumulated during the marriage are treated as exempt from marital division have included social security retirement benefits and portions of personal injury awards from lawsuits relative to pain and suffering. FN14.

ORGANIZING THE INFORMATION

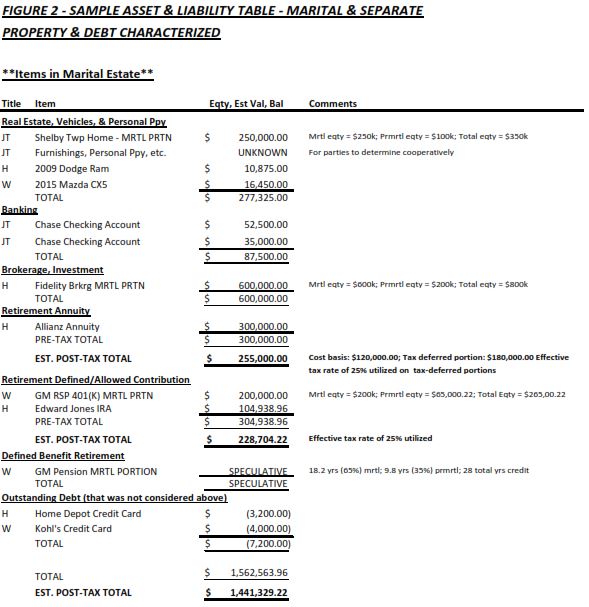

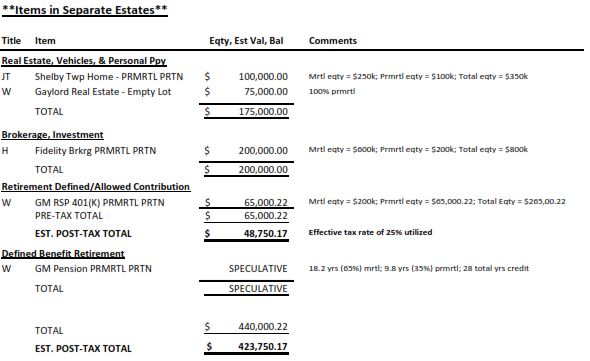

In Figure 1 of part 1 of this series, “Inventory of the Estate – Dividing Property and Debt in a Michigan Divorce,” this author provided a sample asset and liability table at the end of the inventory stage of the analysis.

Next, once a party’s divorce lawyer has conducted a characterization analysis on all of the property and debt identified in the inventory stage, it is important for the attorney to update his/her in-house asset and liability table by segregating the separate property and debt from the marital property and debt. Following up on Figure 1 from the previous article, Figure 2 below is an example of an asset and liability table at the end of the characterization stage in a divorce case.

The next article in this series will focus on equitable division of the marital estate upon divorce.

END.

FN1 – Important note: Analyzing property and debt division in divorce, should be done on a case by case basis, it can be complicated and highly fact and law intensive, and there often are subcategories contained in each category of the analysis. Another important note: Depending on the circumstances of a given case, the steps for division may need to occur in a different order than identified in this article, as critical thinking applied to Michigan’s convoluted framework on this topic dictates. Each case is different.

FN2 – Landry-Chan v Poh Huat Chan, unpublished opinion per curiam, Michigan Court of Appeals, issued April 20, 2017 (Docket No 331977).

FN3 – Id at Lexis *56-75.

FN4 – E.g. see Cunningham v Cunningham, 289 Mich App 195; 795 NW 2d 826 (2010), generally.

FN5 – E.g., see Ponte v Ponte, unpublished opinion per curiam, Michigan Court of Appeals, issued July 24, 2008 (Docket No 274667).

FN 6 – See McNamara v Horner (Before Remand), 249 Mich App 177; 642 NW2d 385 (2002); McNamara v Horner (After Remand), 255 Mich App 667; 662 NW2d 436 (2003). Also see Boots v Vogel-Boots, unpublished opinion per curiam, Michigan Court of Appeals, issued February 5, 2013 (Docket No 317229).

FN7 – See Reeves v Reeves, 226 Mich App 490; 575 NW2d 1 (1997).

FN8 – See Maher v Maher, unpublished per curiam, Michigan Court of Appeals, issued April 20, 2010 (Docket No. 287309). Also see Dart v Dart, 460 Mich 573, 597 NW2d (1999); Reeves v Reeves,226 Mich App 490, 575 NW2d 1 (1997); Grotelueschen v Grotelueschen, 113 Mich App 395; 318 NW2d 227 (1982).

FN9 – See Reeves v Reeves, 226 Mich App 490; 575 NW2d 1 (1997); Korth v Korth, 256 Mich App 286; 662 NW2d 111 (2003).

FN10 – See Szukala v Szukala, unpublished per curiam, Michigan Court of Appeals, issued June 22, 2010 (Docket No 289456).

FN11 – See Hanaway v Hanaway, 208 Mich App 278; 527 NW2d 792 (1995).

FN12 – See Dart v Dart, 460 Mich 573; 597 NW2d 82 (1999); Reeves v Reeves, 226 Mich App 490; 575 NW2d 1 (1997).

FN13 – At 10 USC §1408.

FN14. See Lee v Lee, 191 Mich App 73; 477 NW2d 429 (1991), regarding personal injury awards relative to pain and suffering. See 42 USC §407(a); Biondo v Biondo, 291 Mich App 720, 809 NW2d 397 (2011), regarding social security retirement benefits.

******************************************************************************

Please note that this article is intended to be academic in nature. Its purpose is to serve as a memorialization of research as well as invoke community discussion. This article shall not constitute legal advice. It does not create an attorney-client relationship. Legal advice should be given on a case-by-case basis, as its accuracy is relative to the timing and particular facts of the given matter. It is important to always consult an attorney regarding legal matters.

******************************************************************************

I am Dennis M. Germain, a Michigan family law attorney who promotes fair resolutions to domestic relations matters. I primarily practice in Macomb County, Wayne County, and Oakland County, Michigan. My office is in Shelby Township, Michigan. My office and contact information is listed as follows:

www.bestinterestlaw.com

Best Interest Law

48639 Hayes Road, Suite A

Shelby Township, MI 48315

Ph: (586) 219-6454

Fax: (586) 439-0404

Email: dennis.germain@bestinterestlaw.com

Ask a Family Law Attorney

Ask a Family Law Attorney

Recent Featured Articles

Recent Featured Articles

Client Testimonials

Client Testimonials