By: Dennis M. Germain, Macomb Family Law and Divorce Lawyer

INTRODUCTION

This article is Part Three of the four part series, “Dividing Property & Debt in a Michigan Divorce.” With regard to division of property and debt in divorce, clients sometimes ask me:

“Will my husband get 50% of my assets in a divorce?”

“Do I get to keep my separate property in the divorce?”

“Will I have to take on my wife’s debt in a divorce?”

“What happens to my house in the divorce case?”

“Can I be awarded more than 50% of the marital estate in the divorce?”

This article aims to offer some guidance toward addressing these inquiries. However, adequately addressing these inquiries requires marching through a four stage analysis. The first article in this series concentrated on inventory (itemizing and valuing) of the parties’ property and debt in a divorce (part one). The second article in this series concentrated on characterization of items of property and debt as marital or separate in a divorce (part two). This article, part three, concentrates on the equitable division of marital items of property and debt in a divorce. The fourth and final article will focus on identifying if and when invasion of a party’s separate estate might be applicable (part four). FN1.

SEGREGATION OF SEPARATE ITEMS

Before getting into the equitable division stage of the analysis, it is essential to recall the principles from the previous article regarding characterization of items of property and debt. As discussed therein, all items or portions thereof determined to be “marital” property and debt are subject to equitable division at this stage. FN2. All items or portions thereof determined to be “separate” property and debt are not subject to equitable division at this stage. FN3.

Once we determine what items of property and debt of a divorcing couple are “marital” and what items are “separate,” we take all of the separate items, temporarily presume that each separate item will be awarded back to its exclusive owner, and we will later analyze whether an exception applies that may require division of the separate items too. At this current stage, a prudent attorney will have already created an asset and liability table that itemizes all of the marital property and debt subject to division, and will have already determined what he/she believes are the separate items to be segregated. We are now only focusing on equitable division of the marital items.

EQUITABLE DIVISION – STARTING WITH A “ROUGHLY CONGRUENT DIVISION”

Because the Michigan Compiled Laws are not incredibly thorough on this topic, attorneys and domestic relations courts primarily look to case law standards for tackling the equitable division stage. With regard to dividing the marital property and debt in a Michigan Divorce, a court has a duty to make a decision that is equitable under all of the circumstances. FN4. But what does “equitable” mean in the context of divorce? It does not necessarily mean equal division of the marital estate. FN5. Rather “equitable” essentially refers to a fair division after considering all pertinent factors. The Michigan Supreme Court has determined that the pertinent factors to be considered and applied to the facts of a case may include but are not limited to the following factors:

- The duration of the marriage;

- The contributions of the parties to the joint estate;

- The age of the parties;

- The health of the parties;

- The life status of the parties;

- The necessities and circumstances of the parties;

- The earning abilities of the parties;

- The past relations and conduct of the parties (e.g. “fault”);

- General principles of equity. FN6.

Other factors, within a court’s discretion, may be considered, and may contrast depending on the facts and circumstances of each case. FN7. Some factors may not be pertinent in a given case, and a court may apply greater weight to some factors (within the court’s reasonable discretion) depending on the circumstances of the case. FN8. In general, there is not a “rigid framework” for assessing the factors, and “strict mathematical formulations” for determining property and debt division are essentially prohibited. FN9.

Although a “rigid framework” and “strict mathematical formulations” are apparently not allowed, and although “equitable” division apparently does not have to mean “equal” division under the law, in practice, equal division is still often the starting point of the equitable division analysis, as the Michigan Court of Appeals has held that an equitable division is one that is “roughly congruent,” and that, “[a]ny significant departure from that goal should be supported by a clear exposition of the trial court’s rationale.” FN10. The Michigan Court of Appeals has described this concept as the “presumption of congruence.” FN11.

ACTUALLY ACHIEVING 50%/50% DIVISION

In an attempt to follow the general legal path that the upper courts of Michigan have provided us, when handling a case, this author will typically, first, strive to identify what equal division of the marital estate looks like on paper, and, second, apply the above-listed factors to the circumstances of the case to determine if departing from equal division is potentially justifiable. At this stage, we are now focusing on identifying a 50% / 50% division of the marital estate.

Depending on the flexibility of a family’s marital estate, there may be multiple ways to achieve equal division. In other cases, there may only be limited options available toward achieving equal division. In some cases, equal division may only be achieved by selling or liquidating certain assets. Depending on the circumstances, one party might need a method of division that preserves his/her access to post-tax cash. Additionally, attempting to equalize a marital estate amidst the existence of debt, and real estate, investment, retirement, tax-deferred, or other potentially complex assets can require careful analysis and investigation. Some examples of common concerns are listed below.

Division of Tax Deferred Assets

One concern is that a party might not want to equalize post-tax assets against tax-deferred funds held in a 401(k) because the former has already been taxed and the latter will later be subject to taxation. I.e., a true 50% / 50% division may not actually be realized if divorcing parties are using figurative apples to offset figurative oranges.

Division of Separately Managed Plans

Another concern could arise if, for example, a wife has a retirement plan with assets valued at $100,000.00 that is well managed and has historically realized great gains, versus a husband who also has a retirement plan with assets valued at $100,000.00 that has historically under-performed. In such a case, the husband might want to argue that, rather than each party being awarded 100% of his/her respective retirement plan, each party should instead be awarded 50% of each of the two plans.

Division of Investment Accounts

With investment accounts subject to capital gains, parties may want to consider dividing all marital holdings under each account on a proportional basis to ensure that one party is not dis-proportionally assuming all of the potential capital gains taxation. When proportional division is not feasible, and if the stakes are high enough, an family law attorney and his/her client might consider seeking the assistance of a domestic relations CPA to assist in identifying favorable alternate options.

Division of Real Estate

When it comes to dividing interests in a home or other real estate, there are a variety of concerns that need to be addressed. For example, if one party hopes to be awarded 100% of the marital interests in a divorcing couple’s home, it will likely be necessary for the other party to be awarded a counterbalancing equity buyout. If there is not enough flexibility in the marital estate to permit one party to keep the home and award the other party an equity buyout sufficient to satisfy equal division of the marital estate, the parties will likely have to sell the marital home and divide the net proceeds.

Furthermore, occupancy rights, sale provisions, closing costs, the apportioning of assumption of liens, encumbrances, ownership expenses, and occupancy expenses, the removal of a party’s name from third party liability (most importantly mortgage liability), the conveyance of title on the property, the assignment of insurance and any escrow balance, the apportionment of income tax and real estate tax benefits and responsibilities, the application of security mechanisms to ensure proper performance by the parties, and many other issues, may have to be addressed to ensure that a divorcing party’s rights are adequately protected.

Division of Pensions

With pensions (or hybrid retirement plans), rather than trying to value a pension (which typically requires great speculation) and offsetting its value against assets differing in kind, parties may instead want to agree to divide the future benefit payable from the credited marital portion of the pension.

Division of Credit Card Debt

Another concern could arise if, for example, a husband had an outstanding credit card debt of $20,000.00 in his sole name subject to an 8% interest rate, versus a wife who had an outstanding credit card debt of $20,000.00 in her sole name subject to an 18% interest rate. In such a case, rather than each party assuming 100% of his/her respective credit card debt or each party assuming 50% of each of the two items of credit card debt (thereby leaving each party to have to trust that the other party will properly pay on a portion of debt that is not in the other party’s name), the parties might instead want to use marital assets (or to liquidate marital assets) to pay off the debt as part of their divorce settlement agreement.

Of Note

This author asserts that proportional in-kind division, across the board, is most often going to achieve the fairest version of equalization. When such a division is not possible, practical, or fair, it is very important for a family law attorney to take the time to understand the nature of the property and debt subject to division, and to use critical thinking when coming up with proposals for fair division.

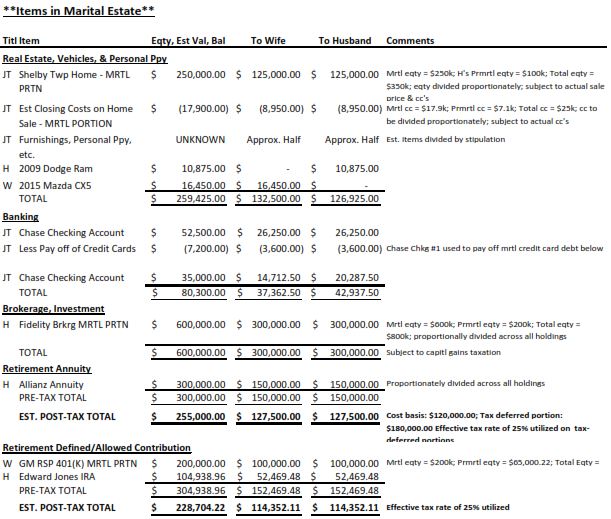

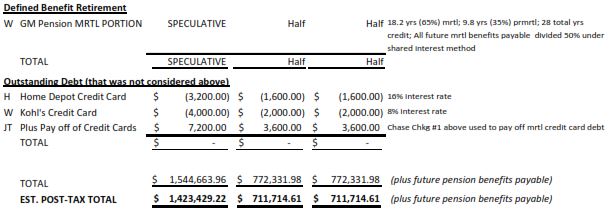

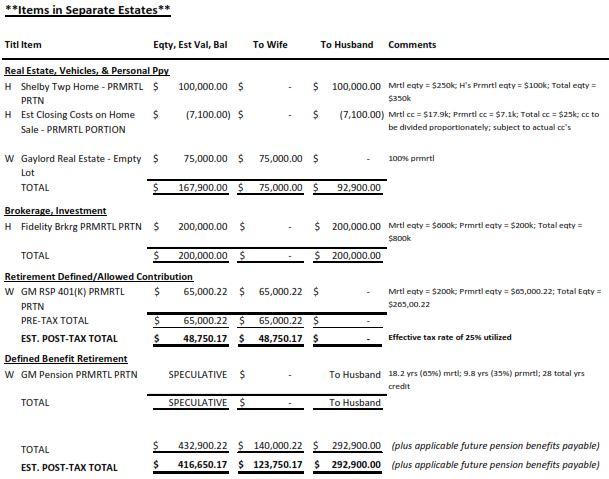

ORGANIZING THE INFORMATION

To organize a proposed equal division, a prudent family law attorney should work with his/her client to draft a sample allocation table (or multiple versions) which aims to portray a 50% / 50% division of the divorcing parties’ marital estate. E.g., if the parties have a positive $100,000.00 of marital property and a negative $50,000.00 of marital debt, each party should expect a bottom line award from the divorce of $25,000.00 at this stage. Creating allocation tables is very important for analyzing property and debt division because it is impossible to identify whether a proposed division of the marital estate is fair without seeing division of the entire estate as a whole. Following up on Figure 1 and Figure 2 from the previous articles, Figure 3 below offers a sample allocation table containing a version of 50% / 50% division.

Figure 3 – Sample Asset & Liability Division Table

DEPARTING FROM 50% / 50% DIVISION

In this author’s experience, it can be difficult to convince a court to significantly depart from 50% / 50% division of the marital estate in one party’s favor. There are some instances where the Michigan Court of Appeals has upheld lower family court decisions that slightly deviated from 50% / 50% division amidst little to no financial connections between the bases for deviating and the actual deviation. However, it is this author’s general opinion that, the more a party’s attorney is able to favorably present a nexus between (a) the circumstances of the parties as pertinent under the above-listed factors, and (b) the financial realities of the parties, the more likely a court will consider assertively departing from 50%/50% in one party’s favor. This author identifies a few examples of this idea below.

Adultery / Fault

For example, if a party engaged in an extramarital affair that had virtually no effect on the value of the marital estate, the adulterer may be credited as being at fault for the breakdown of the marriage, but it is unlikely that a court should punish the adulterer by significantly reducing his/her property award relying solely on the fault factor. FN12. However, if the adulterer has dissipated a large amount of marital assets in pursuit of the affair, the court should be more likely to consider a more assertive departure from equal division of the marital estate in favor of the non-adulterer.

Financial Contribution

For further example, if a wife dutifully fulfilled her agreed-upon marital role as a stay-at-home parent, yet did not produce major earnings, it is unlikely that a court should reduce her award under the contribution factor. FN13. Her contribution was likely very valuable and likely gave the husband opportunities to maximize his financial contribution to the family. On the other hand, if a wife unilaterally refused to make efforts toward satisfying her earning potential during the marriage, while willfully neglecting duties to the family, thereby requiring the husband to both work and handle the domestic duties, and thereby causing the marital estate to be at a value of less than what it would have otherwise been had she faithfully contributed to the marriage, the court should be more likely to consider assertive departure from equal division of the marital estate in favor of the Husband. FN14.

Other Examples

Other examples where a court might consider deviating from equal division could include: a party’s substance abuse or a gambling problem that is causally linked to a lowered value of the marital estate; a party engaging in manipulative transactions to conceal marital assets or thwart fair division of the marital estate; a party suffering from enduring health-related needs that are likely to have a strikingly negative impact on that party’s future finances; a party engaging in egregious spending habits that are causally linked to a lowered value of the marital estate, or the existence of a large amount of marital debt that one party would be able to financially withstand post-divorce and the other party would not. FN15

The next article in this series will focus on Michigan’s legal standards for division of a party’s separate property in divorce, also known as the doctrine of “invasion.”

END.

FN1 – Important note: Analyzing property and debt division in divorce, should be done on a case by case basis, it can be complicated and highly fact and law intensive, and there often are subcategories contained in each category of the analysis. Another important note: Depending on the circumstances of a given case, the steps for division may need to occur in a different order than identified in this article, as critical thinking applied to Michigan’s convoluted framework on this topic dictates. Each case is different.

FN2 – Cunningham v Cunningham, 289 Mich App 195; 795 NW2d 826 (2010); Korth v Korth, 256 Mich App 286; 662 NW2d 111 (2003).

FN3 – Id.

FN4 – Sparks v Sparks, 440 Mich 141, 485 NW2d 893 (1992); Charlton v Charlton, 397 Mich 84, 243 NW2d 261 (1976); Byington v Byington, 224 Mich App 103, 568 NW2d 141 (1997).

FN5 – Christofferson v Christofferson, 363 Mich 421; 109 NW2d 848 (1961).

FN 6 – Sparks v Sparks, 440 Mich 141; 485 NW2d 893 (1992).

FN7 – Id.

FN8 – Id.

FN9 – E.g., see id, citing Hallett v Hallett, 279 Mich 246; 271 NW 748 (1937); Cartwright v Cartwright, 341 Mich 68; 67 NW2d 183 (1954).

FN10 – Jansen v Jansen, 205 Mich App 169, 171, 517 NW2d 275 (1994); Byington v Byington, 224 Mich App 103, 568 NW2d 141 (1997); Knowles v Knowles, 185 Mich App 497; 462 NW2d 777 (1990); McDermott v McDermott, 84 Mich App 39; 269 NW2d 299 (1978).

FN11 – Byington v Byington, 224 Mich App 103, 568 NW2d 141 (1997).

FN12 – See Sparks v Sparks, 440 Mich 141; 485 NW2d 893 (1992).

FN13 – E.g., see Hanaway v Hanaway, 208 Mich App 278; 527 NW2d 792 (1995). Also see McDougal v McDougal, 451 Mich 80; 545 NW2d 357 (1996).

FN14. E.g., see generally Gentry v Gentry, unpublished opinion per curiam, Michigan Court of Appeals, issued August 14, 2014 (Docket No 313666).

FN 15 – E.g., see generally Tierney v Tierney, unpublished opinion per curiam, Michigan Court of Appeals, Decided November 8, 1996 (Docket No 181497); Welling v Welling, 233 Mich App 708; 592 NW2d 822 (1999); Thames v Thames, 191 Mich App 299, 477 NW2d 496 (1991); Wiand v Wiand, 178 Mich App 137, 443 NW2d 464 (1989); Cassidy v Cassidy, 318 Mich App 463, 899 NW2d 65 (2017); Gates v Gates, 256 Mich App 420, 664 NW2d 231 (2003); Zamfir v Zamfir, 92 Mich App 170, 284 NW2d 517 (1979); Sands v Sands, 192 Mich App 698; 482 NW2d 203 (1992); Lesko v Lesko, 184 Mich App 395, 401; 457 NW2d 695 (1990); Stevick v Stevick, unpublished opinion per curiam, Michigan Court of Appeals, decided September 24, 2002 (Docket No 225500).

******************************************************************************

Please note that this article is intended to be academic in nature. Its purpose is to serve as a memorialization of research as well as invoke community discussion. This article shall not constitute legal advice. It does not create an attorney-client relationship. Legal advice should be given on a case-by-case basis, as its accuracy is relative to the timing and particular facts of the given matter. It is important to always consult an attorney regarding legal matters.

******************************************************************************

I am Dennis M. Germain, a Michigan family law attorney who promotes fair resolutions to domestic relations matters. I primarily practice in Macomb County, Wayne County, and Oakland County, Michigan. My office is in Shelby Township, Michigan. My office and contact information is listed as follows:

www.bestinterestlaw.com

Best Interest Law

48639 Hayes Road, Suite 9

Shelby Township, MI 48315

Ph: (586) 219-6454

Fax: (586) 439-0404

Email: dennis.germain@bestinterestlaw.com

Ask a Family Law Attorney

Ask a Family Law Attorney

Recent Featured Articles

Recent Featured Articles

Client Testimonials

Client Testimonials